Astronomers Find Dust Traveling Beyond Its Galaxy

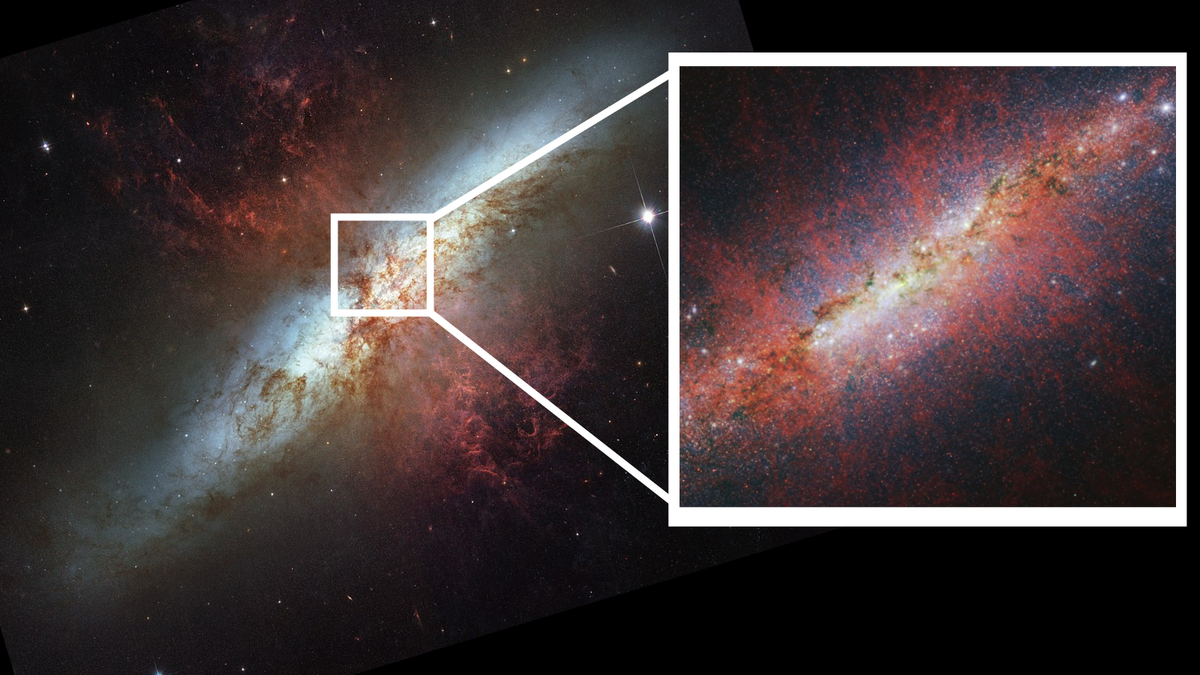

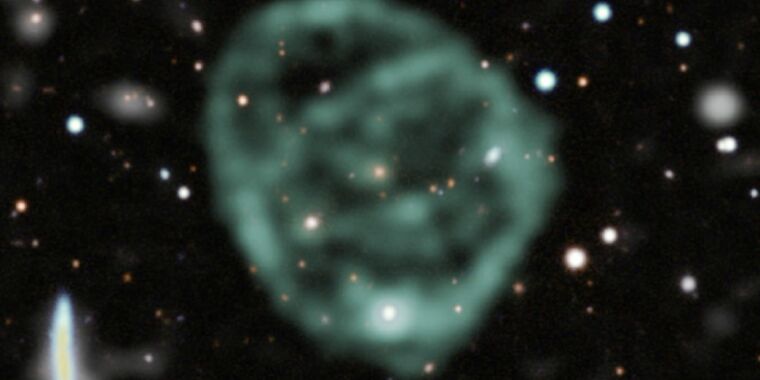

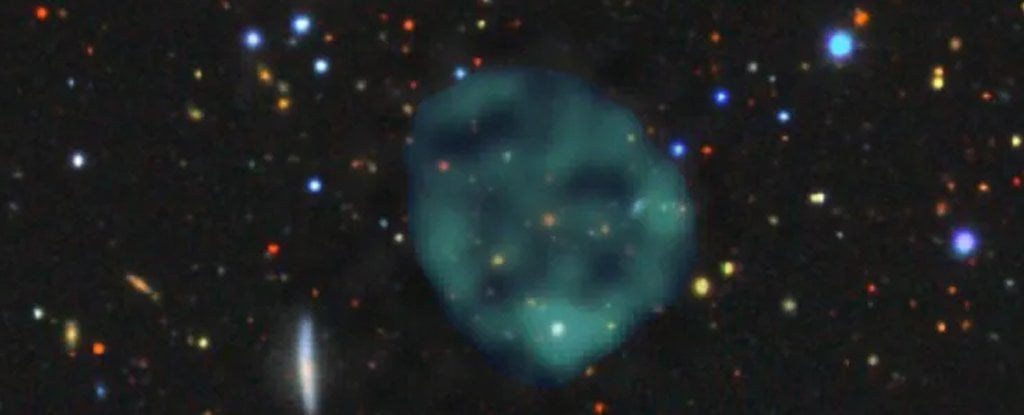

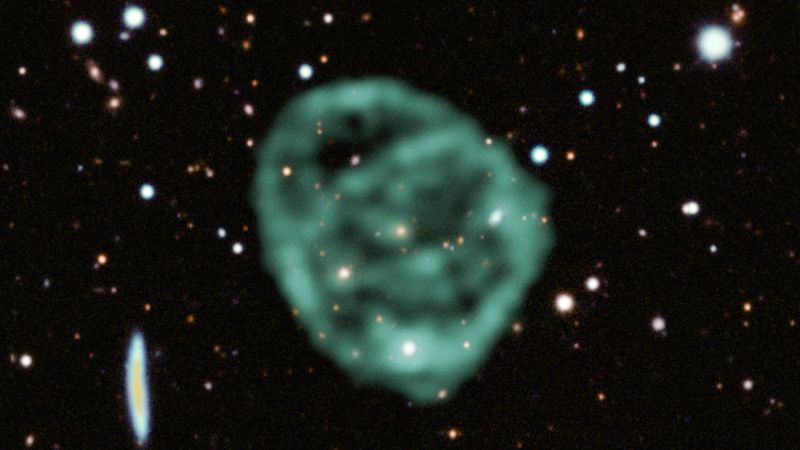

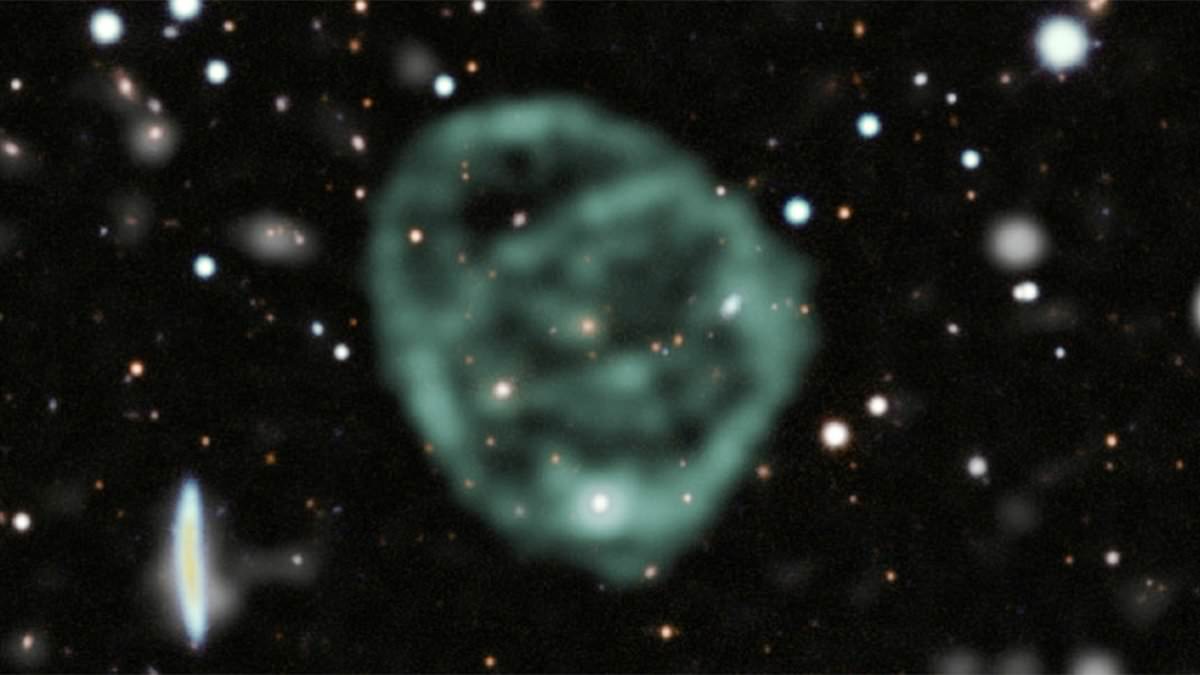

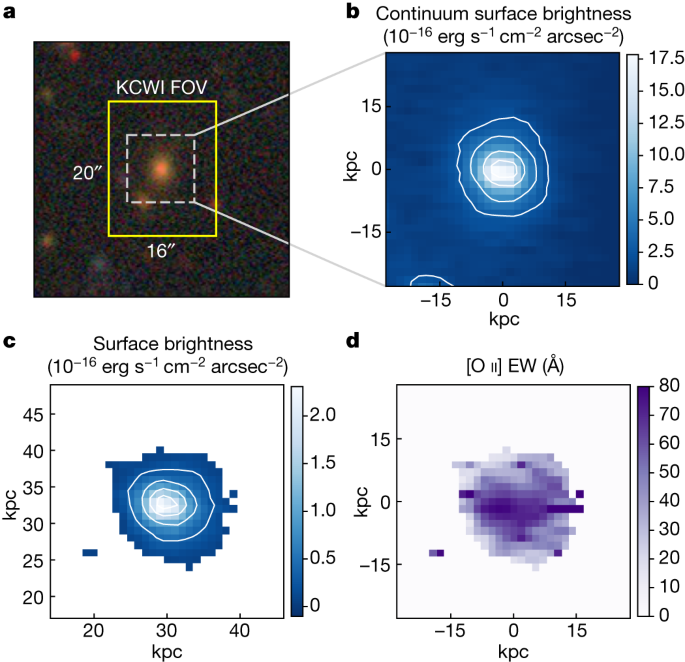

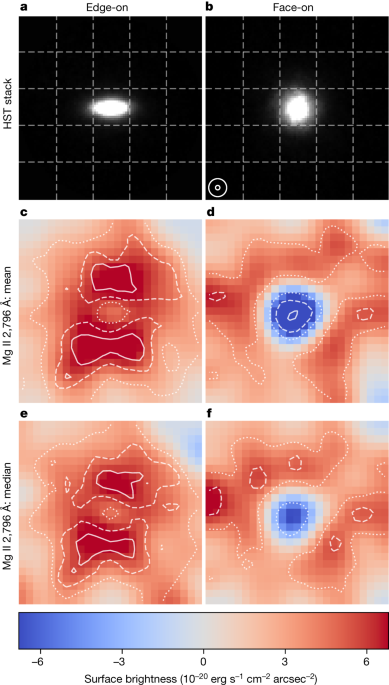

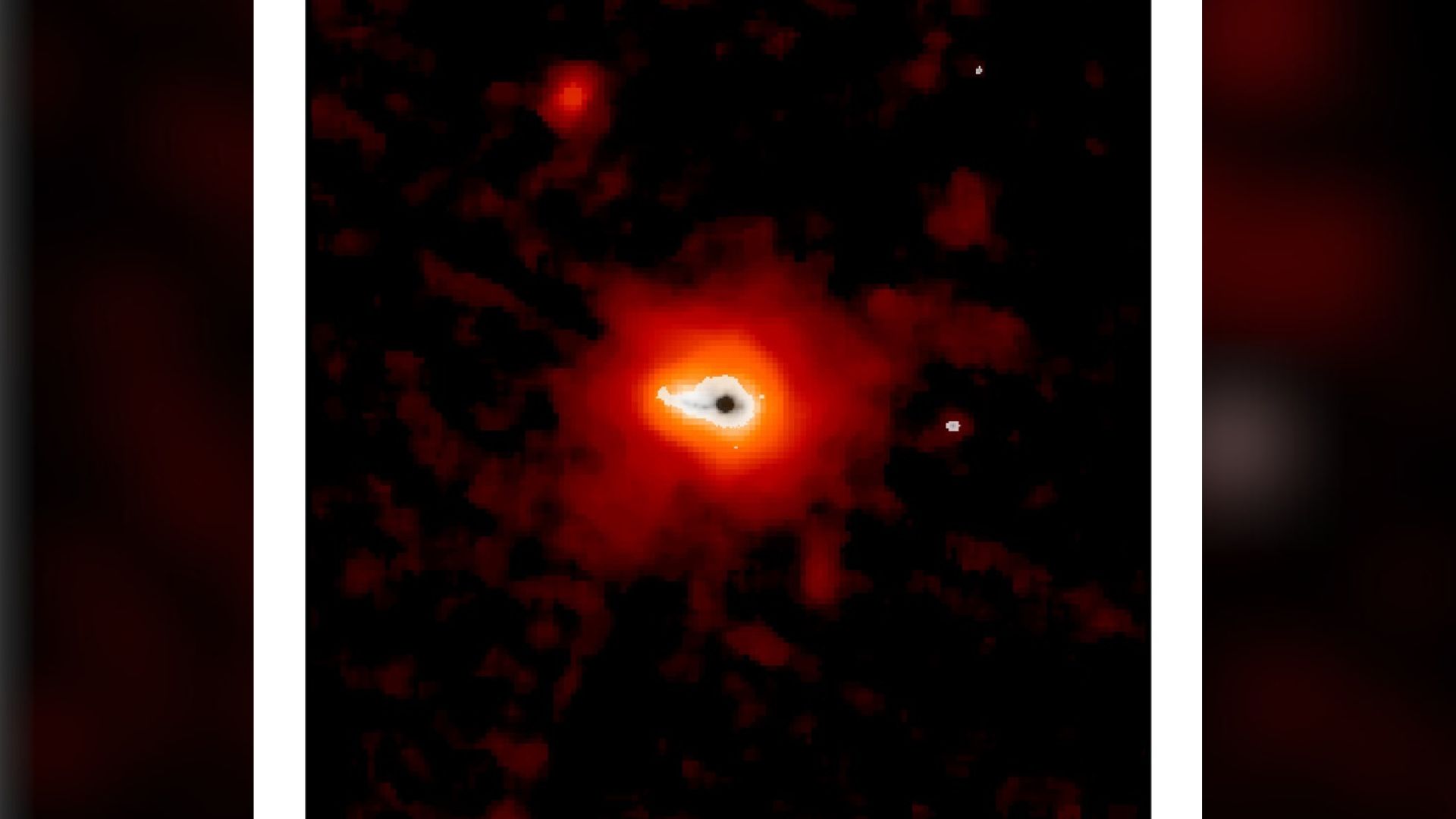

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope discovered tiny dust particles traveling far beyond their galaxy, surviving harsh conditions in the circumgalactic medium, revealing new insights into galaxy evolution and matter recycling through a proposed 'cloud-wind mixing' mechanism.