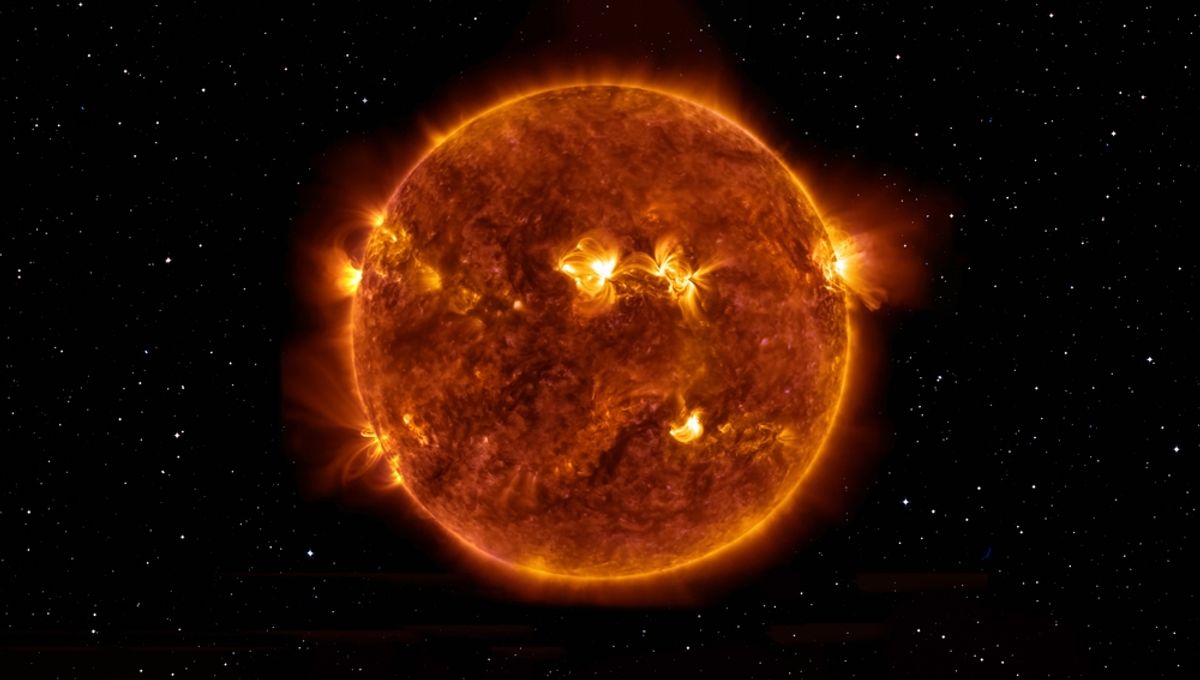

NASA's Parker Probe Reveals New Insights Into the Sun's Atmosphere and Solar Wind

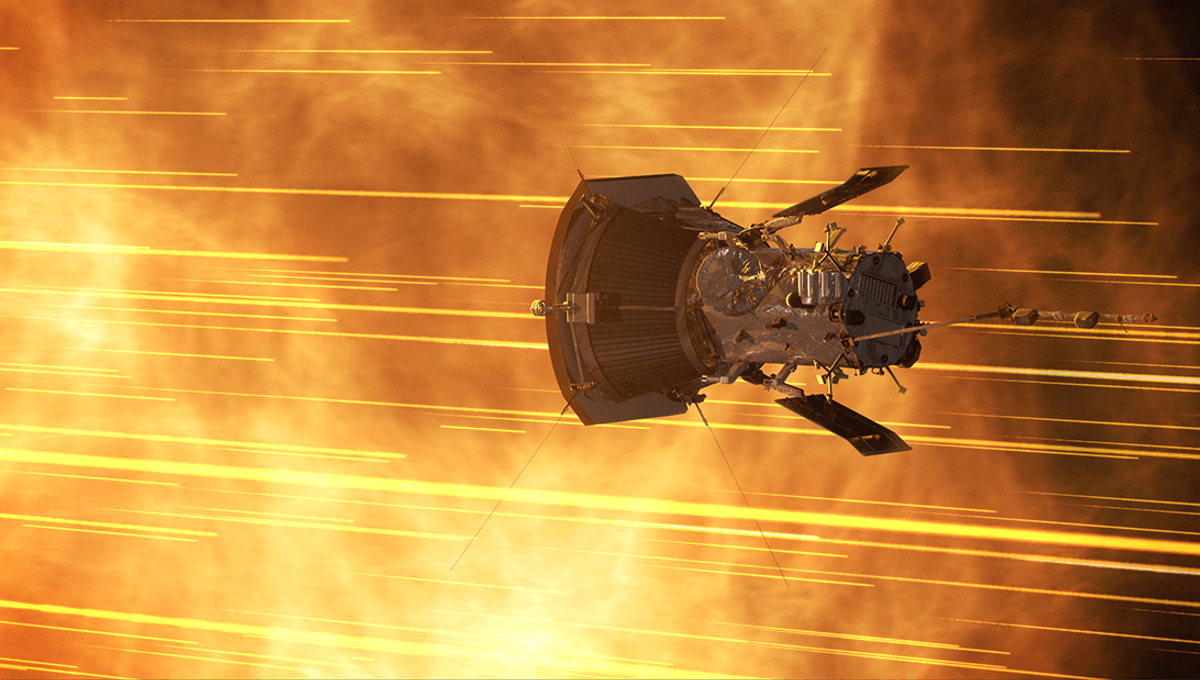

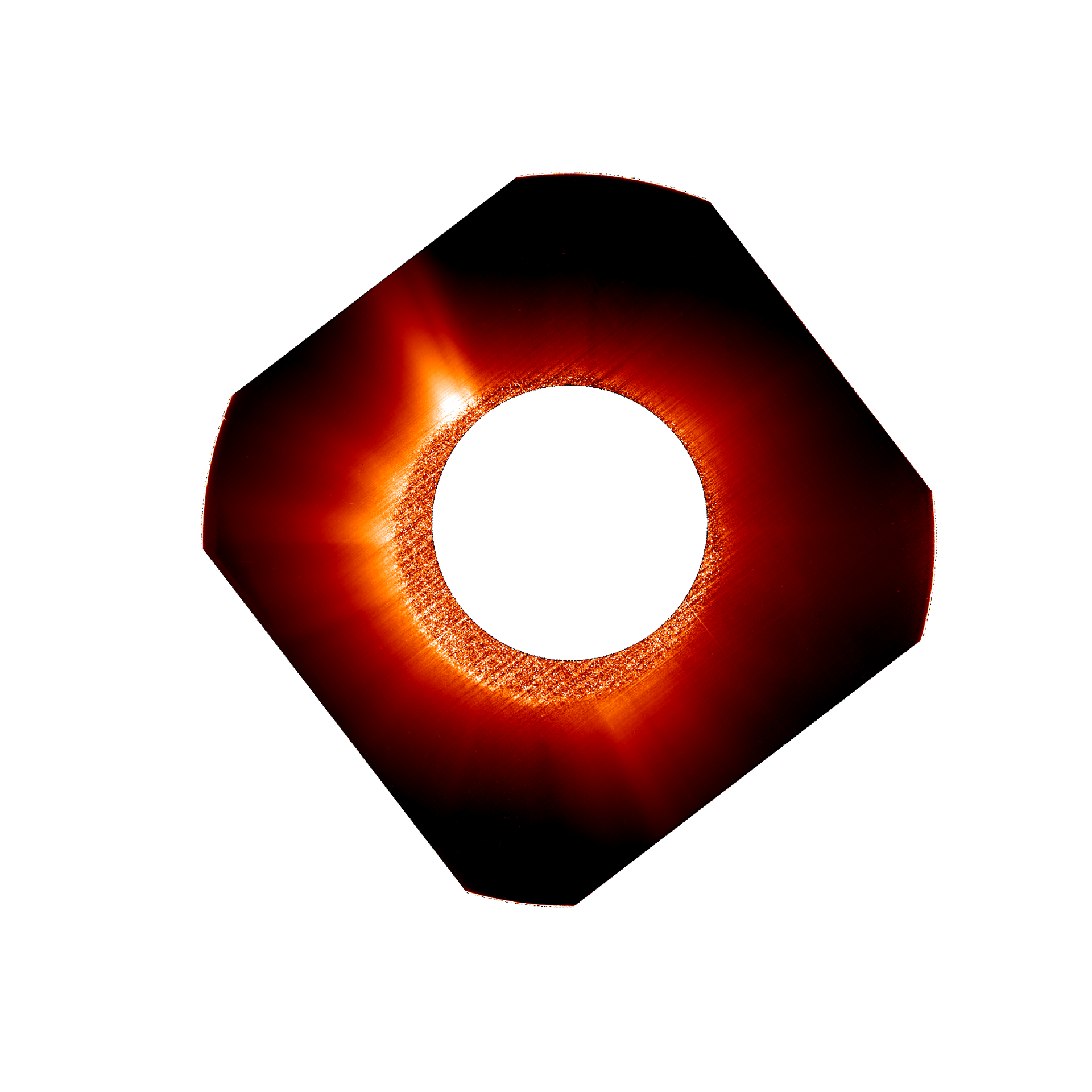

NASA's Parker Solar Probe has found evidence of a 'helicity barrier' in the Sun's atmosphere, which could help explain the long-standing mystery of why the Sun's corona is much hotter than its surface and improve understanding of solar wind acceleration. The study suggests that this barrier influences plasma heating and magnetic fluctuations, with implications for space weather and astrophysics. Further analysis is needed, but the findings are promising for solving key solar physics puzzles.