Lithium in the Brain Sparks a Ten-Year Alzheimer’s Breakthrough

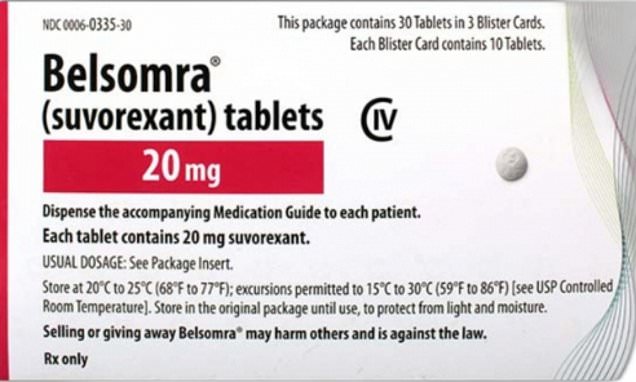

Harvard researchers show lithium naturally exists in the brain and supports neuron function; lithium depletion is an early Alzheimer’s change and is reduced when amyloid plaques bind lithium. In mice, losing brain lithium accelerates disease, while a lithium orotate compound can prevent or reverse pathology, prompting planned clinical trials; researchers caution against self-medicating until trials establish safety and efficacy.