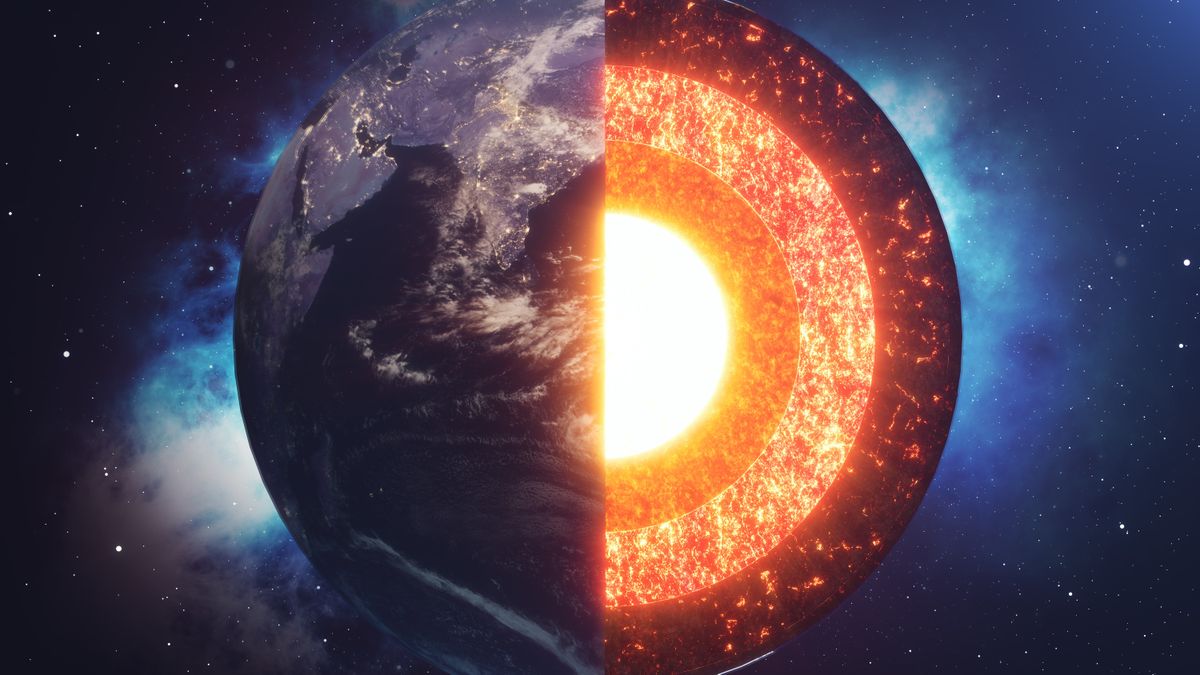

Uranus's Unexpected Warmth Redefines Ice Giant Mysteries

Recent studies confirm that Uranus emits about 12.5% more heat than it receives from the Sun, resolving a long-standing puzzle and suggesting unique internal processes or history, which underscores the need for future missions to better understand this enigmatic planet.