"Plastic-Eating Fungus Discovered in Great Pacific Garbage Patch"

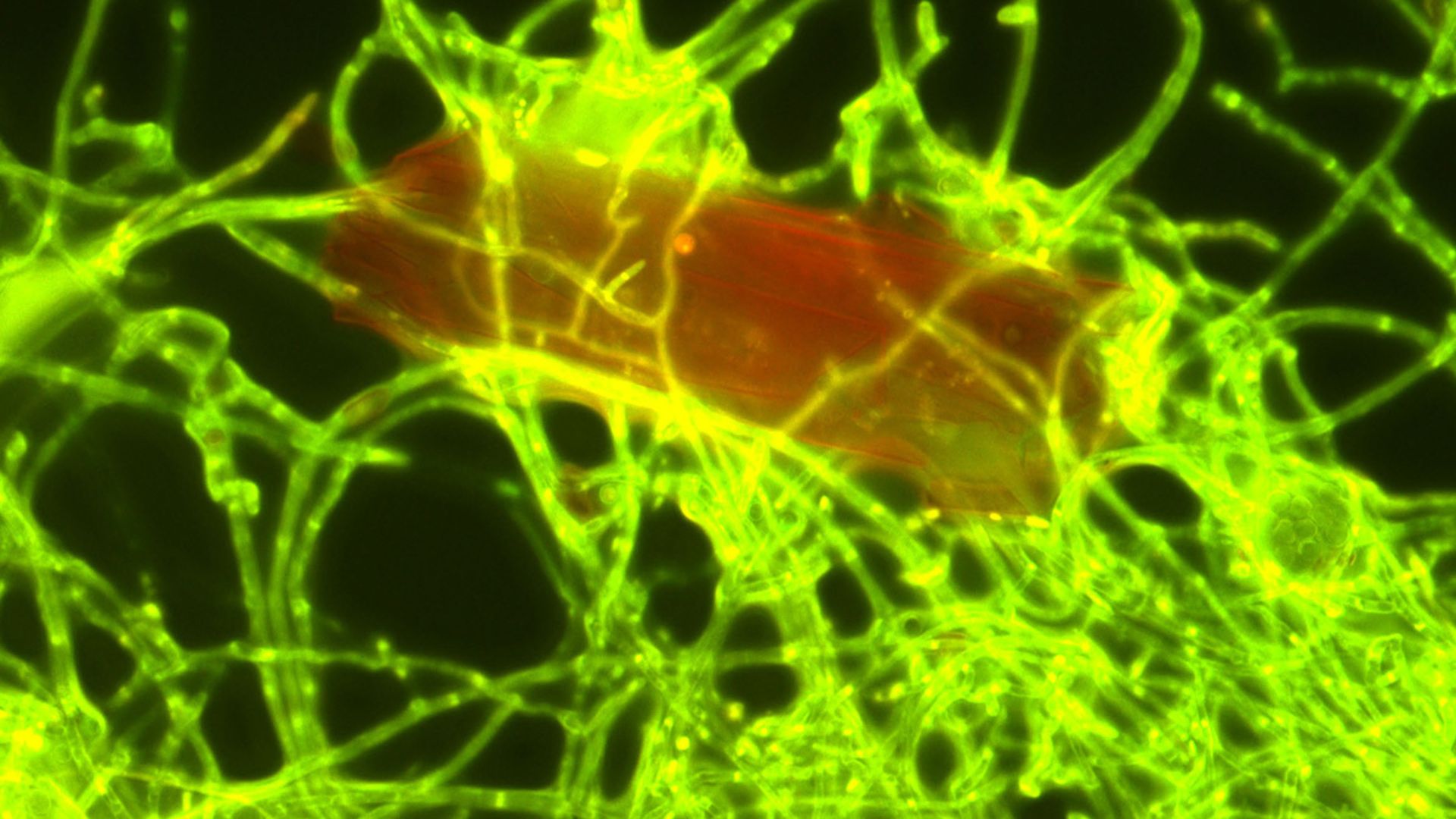

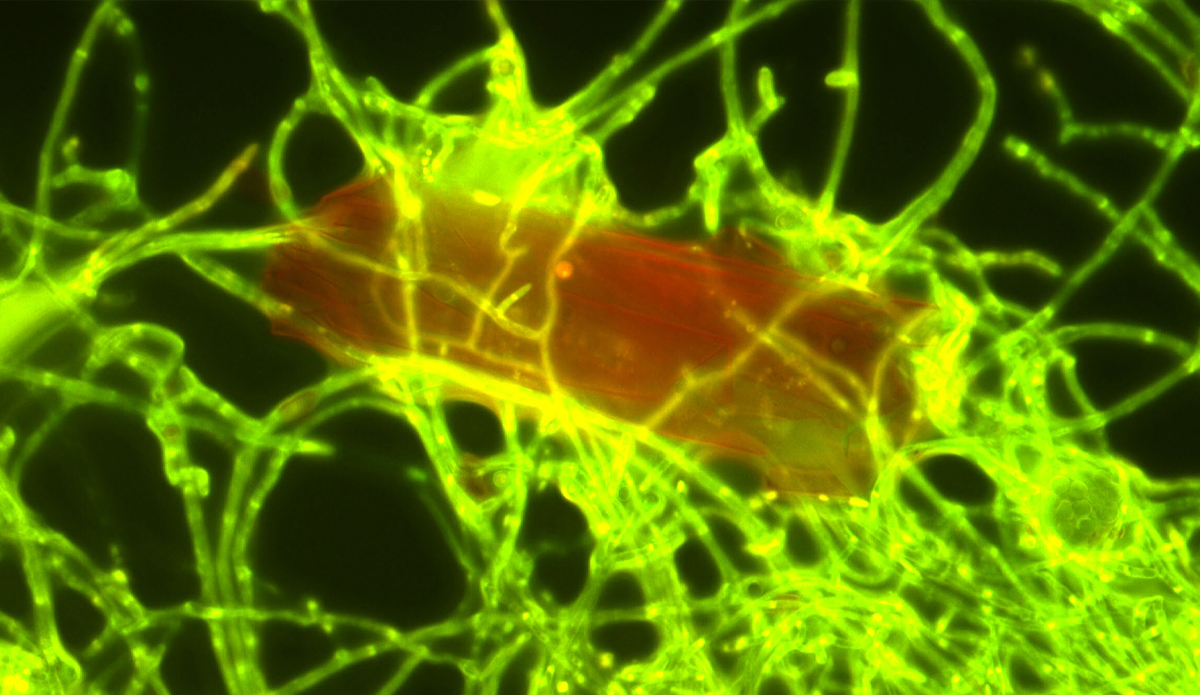

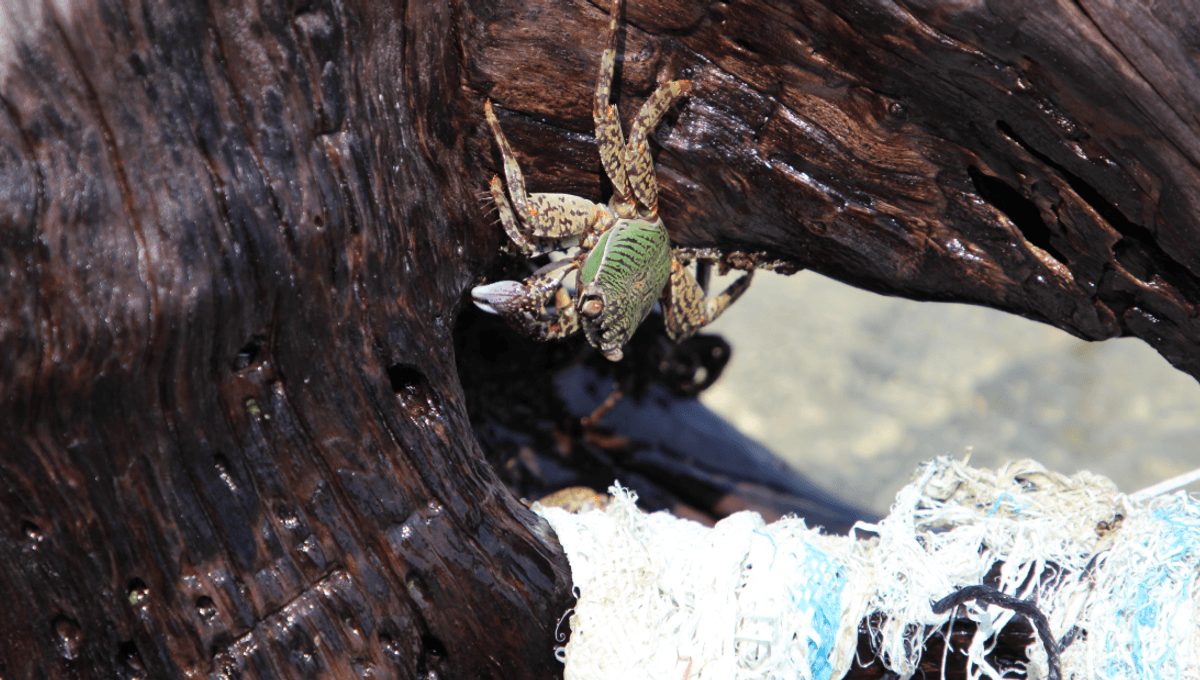

Scientists have discovered a plastic-eating fungus, Parengyodontium album, in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch that can break down UV-exposed polyethylene, the most common plastic. While it works slowly, this fungus offers hope for more effective ocean cleanup methods without harming marine life, highlighting the need for continued reduction of single-use plastics.