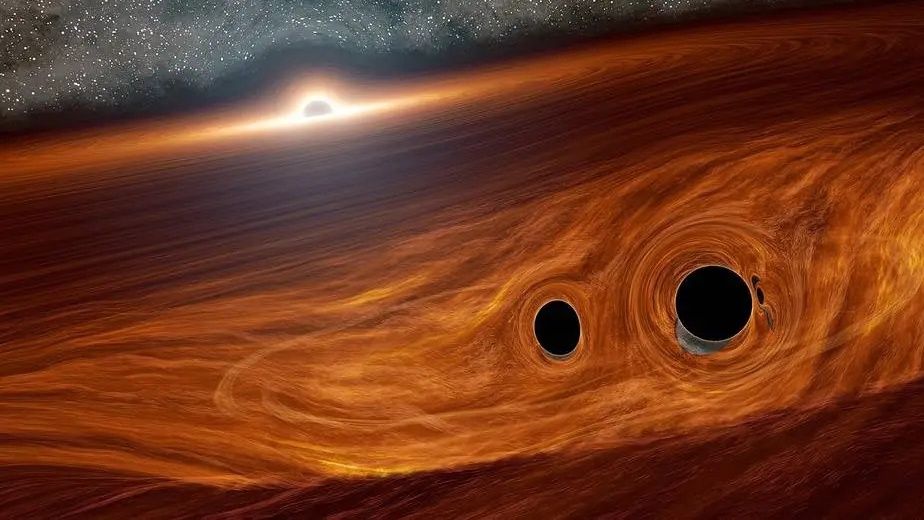

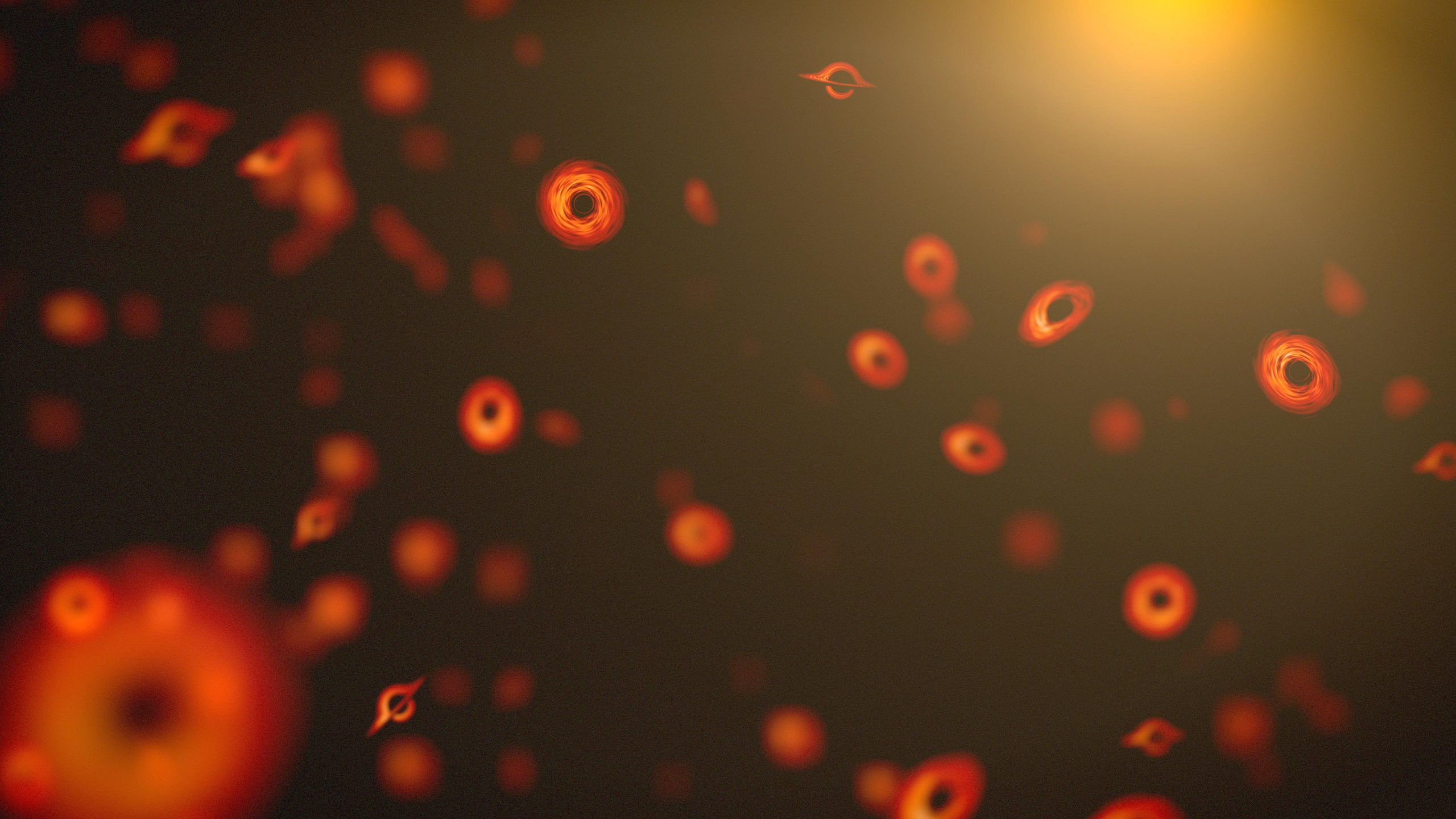

Primordial Black Holes: Hidden Threats in Planets and Everyday Objects

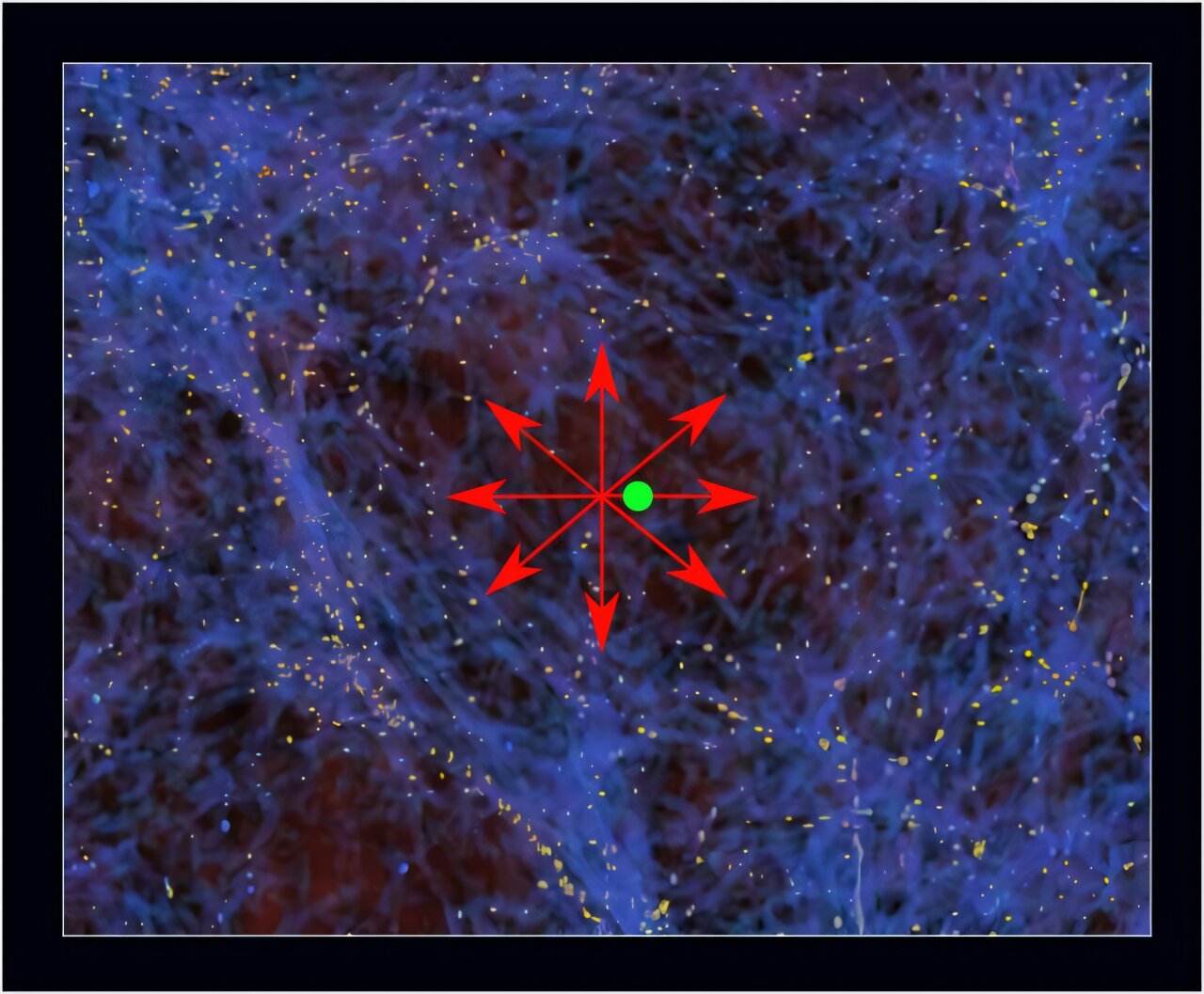

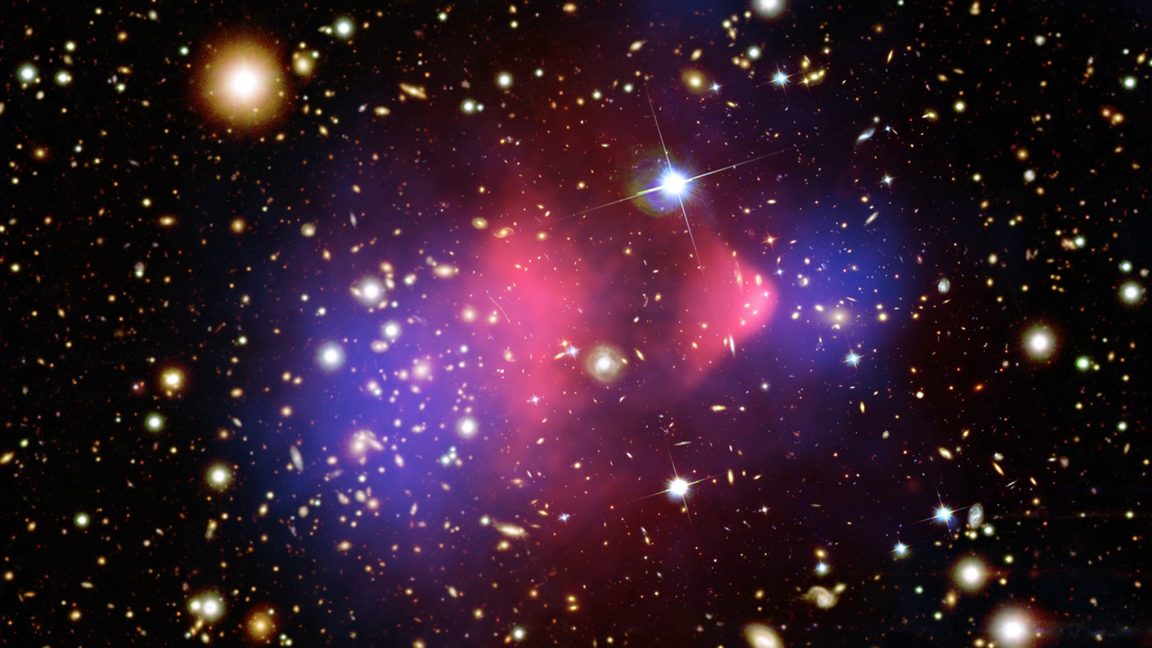

A new theoretical study suggests innovative methods to detect primordial black holes, proposing that these elusive objects could leave signatures such as hollow planetoids in space or microscopic tunnels in earthly materials. The research, co-led by the University at Buffalo, highlights the potential of these low-cost methods to advance our understanding of dark matter, despite the low probability of detection. The study emphasizes the need for creative approaches in the field of astrophysics, as traditional methods have yet to yield direct evidence of primordial black holes.