Scientists Detect Massive Internal Shift Within the Earth

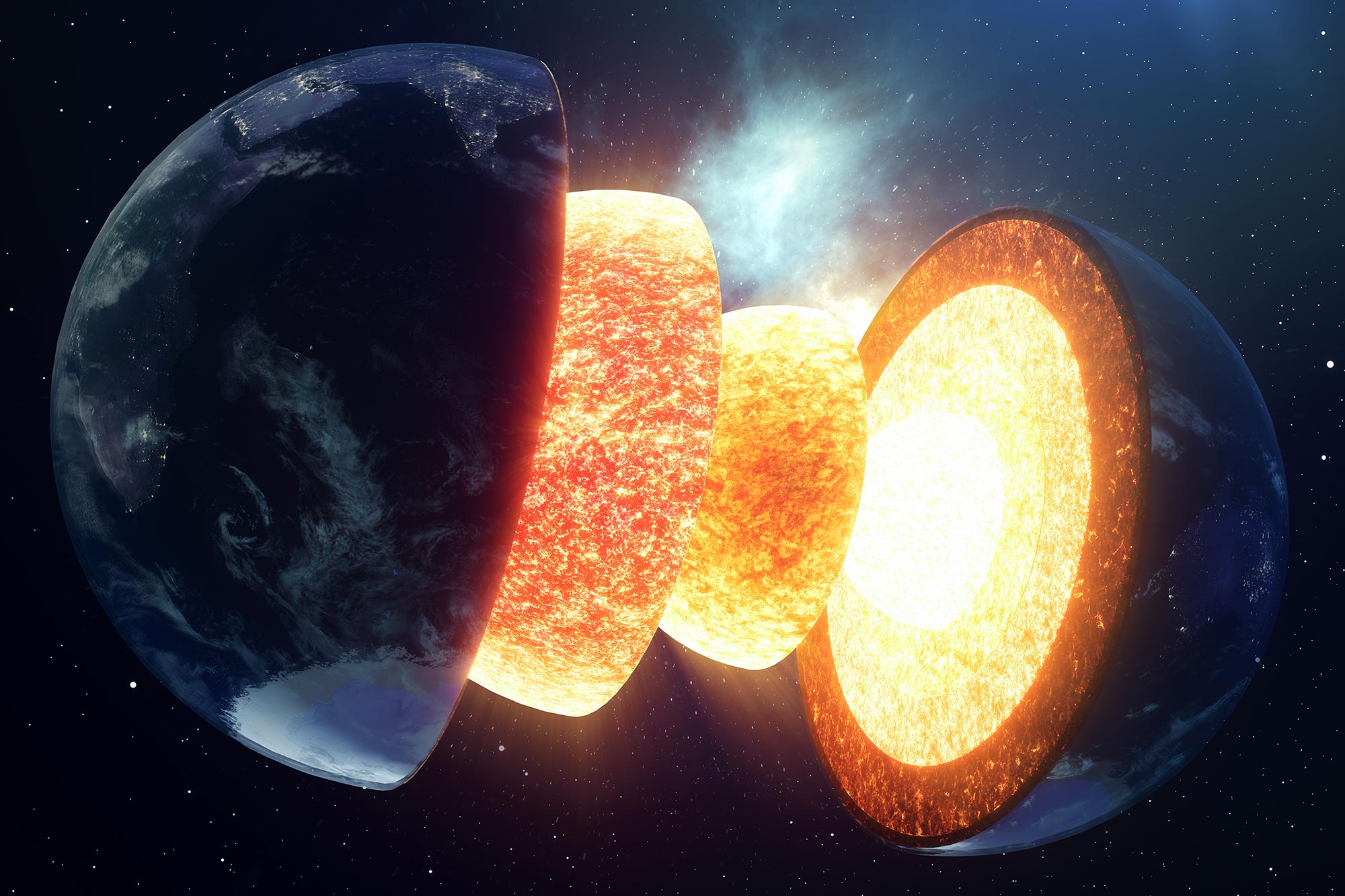

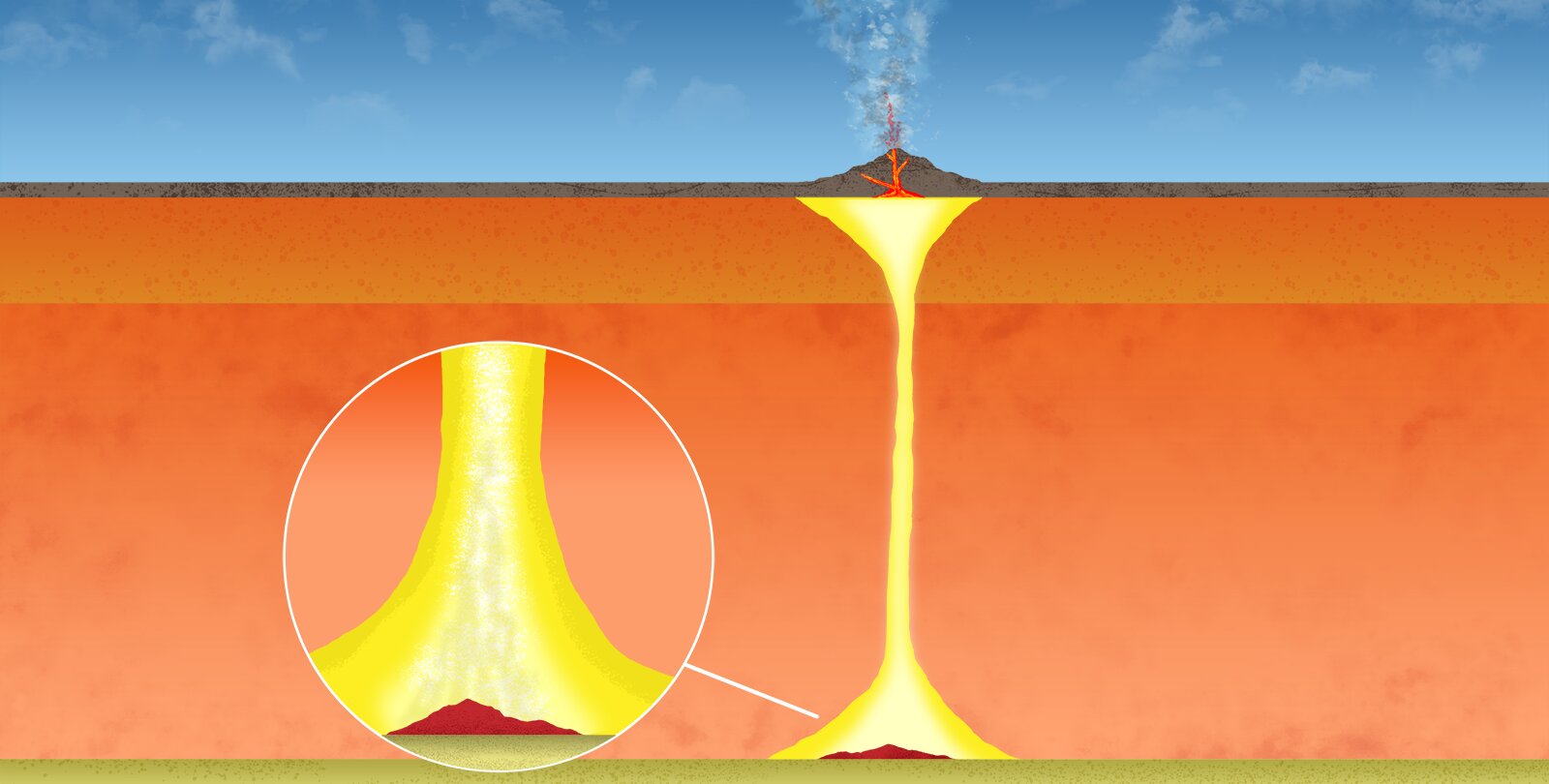

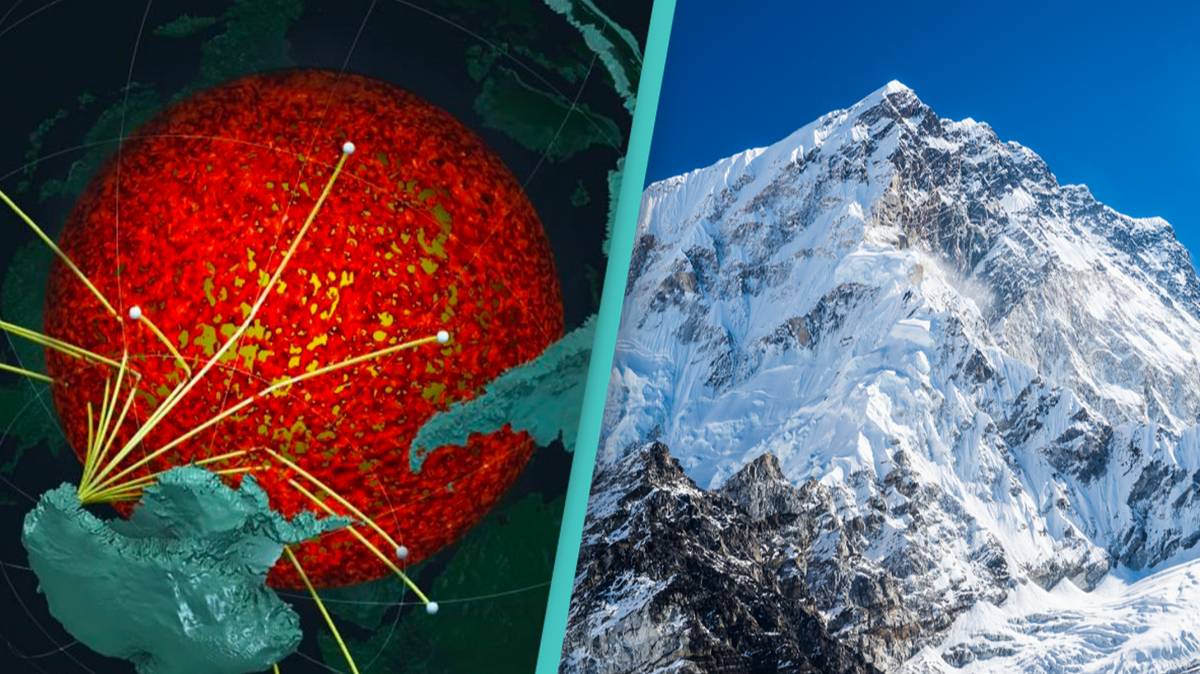

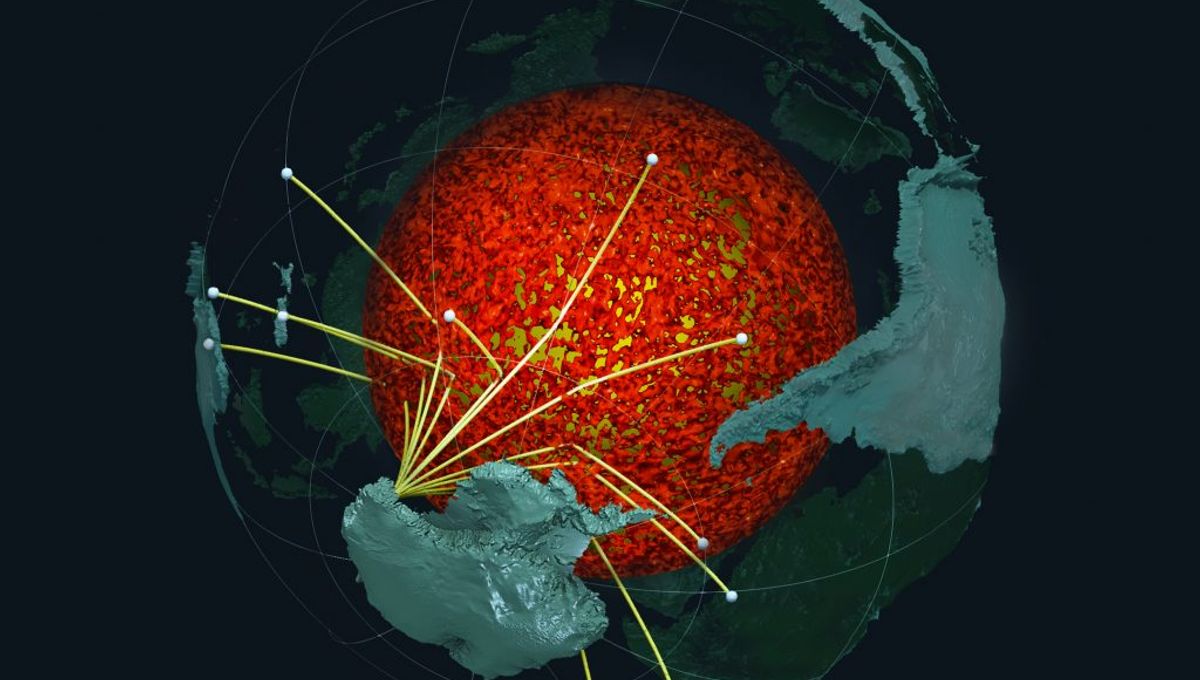

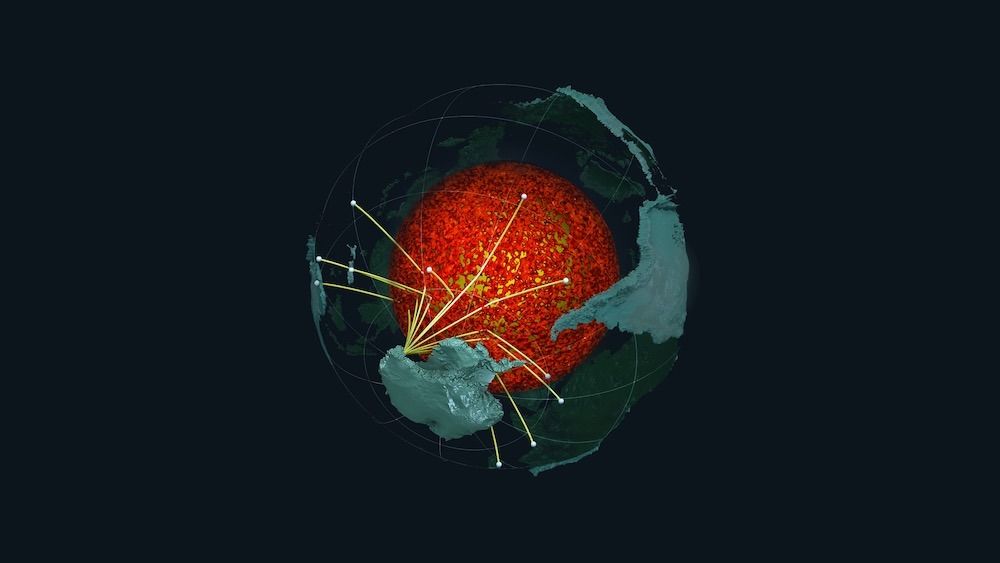

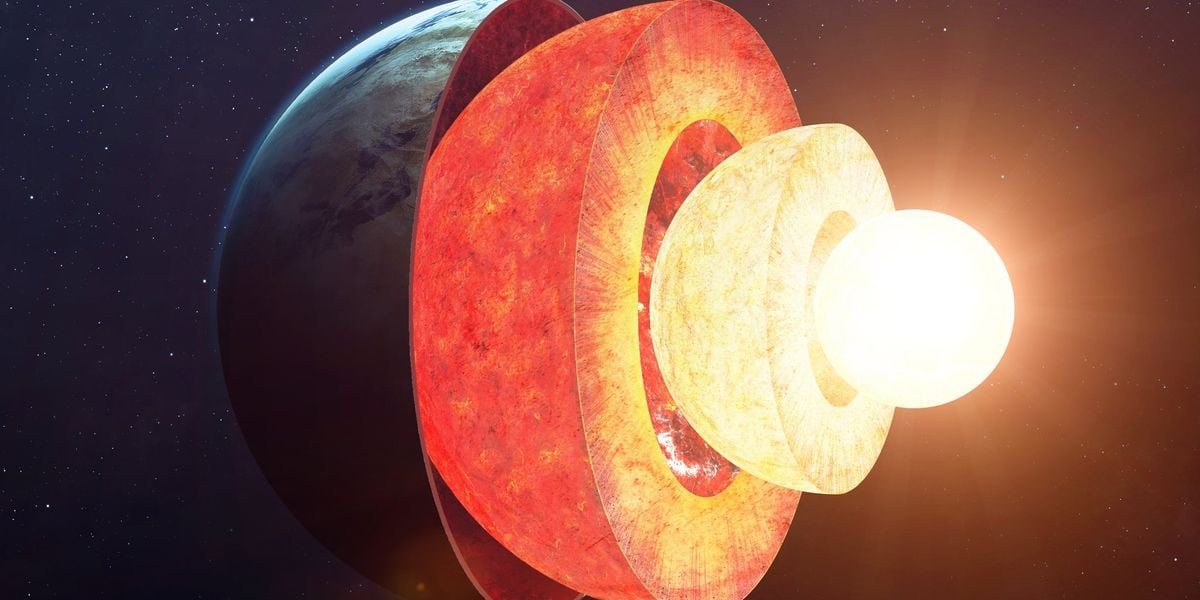

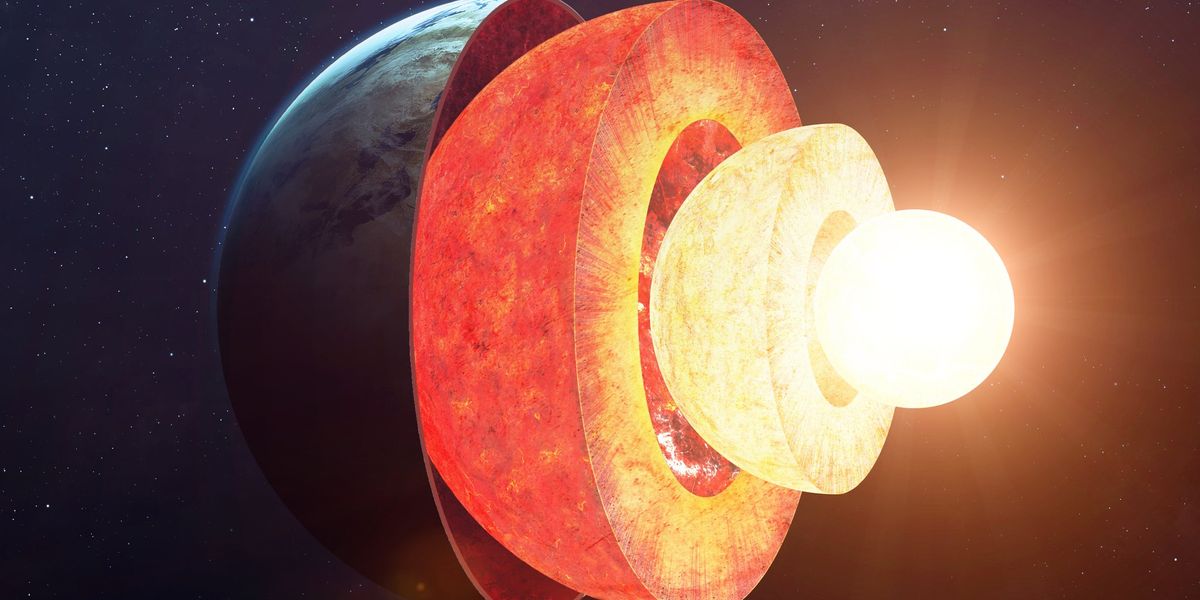

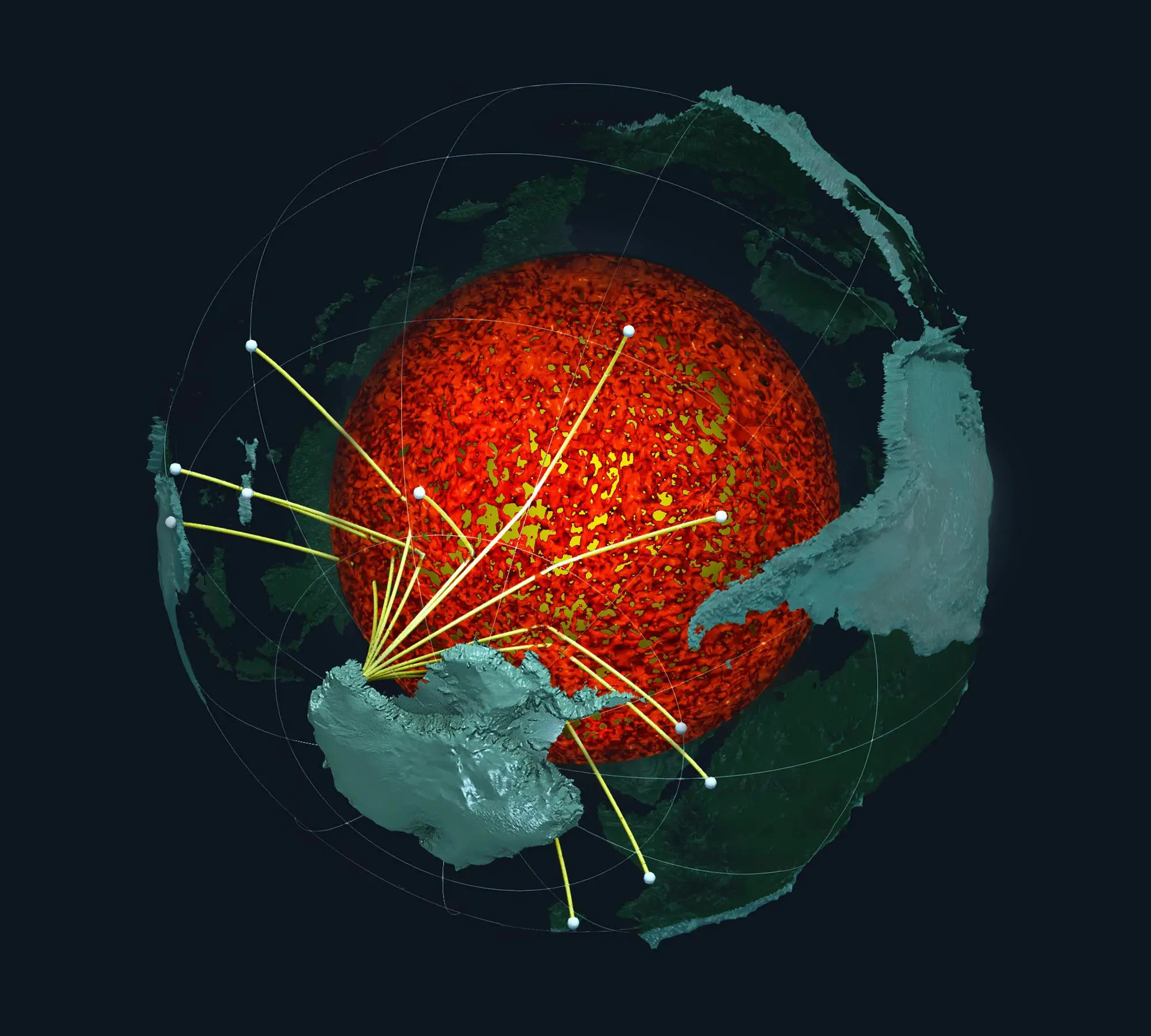

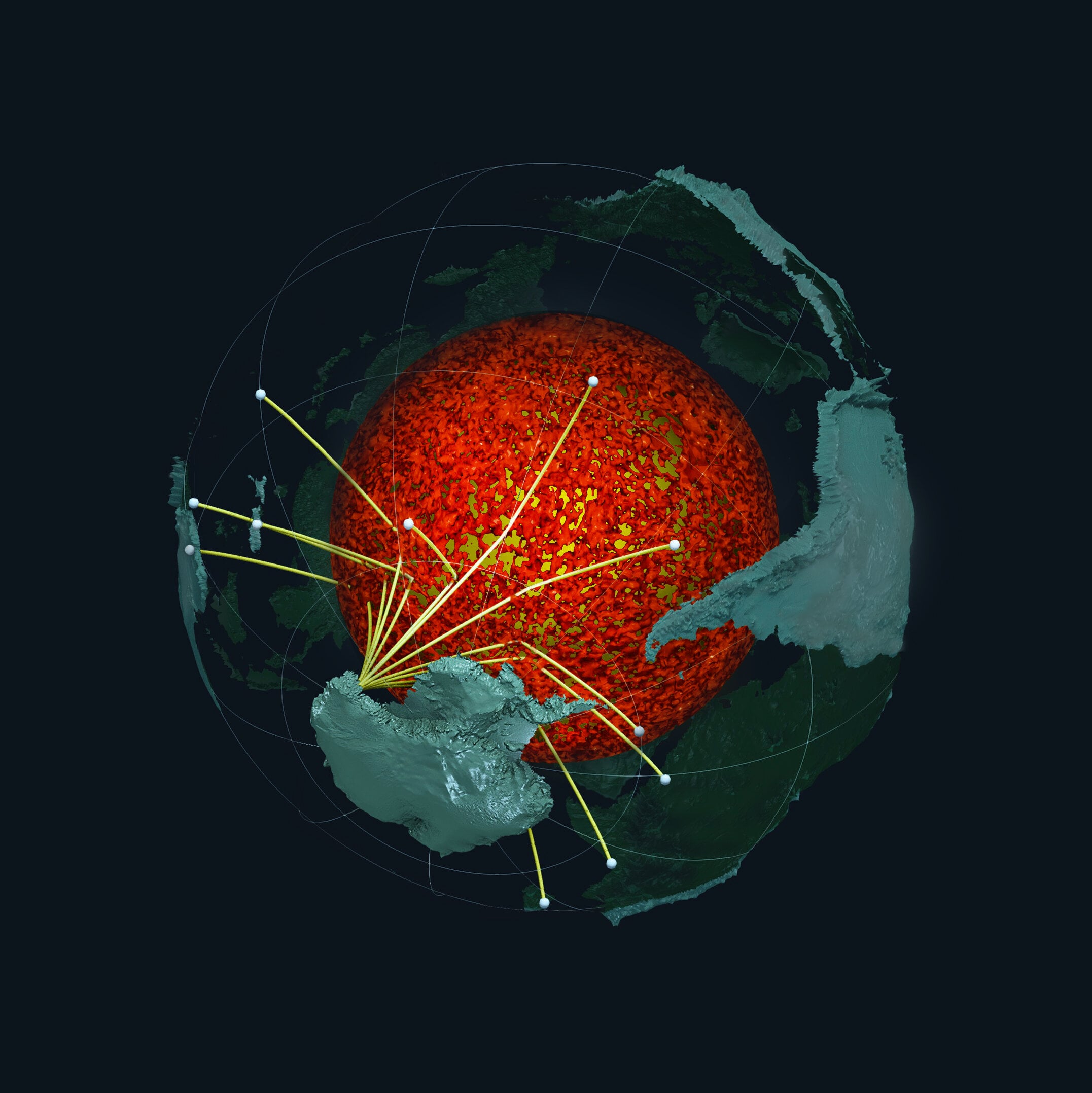

Scientists analyzing data from NASA's GRACE satellites discovered evidence of a massive shift deep within the Earth's interior near the core-mantle boundary, possibly caused by changes in mantle minerals like perovskite, which may have influenced Earth's magnetic field and caused a geomagnetic jerk around 2007. They plan to use data from the follow-up GRACE-FO mission to further investigate these deep Earth processes.