Revised Models Challenge Century-Old Himalayas Theory

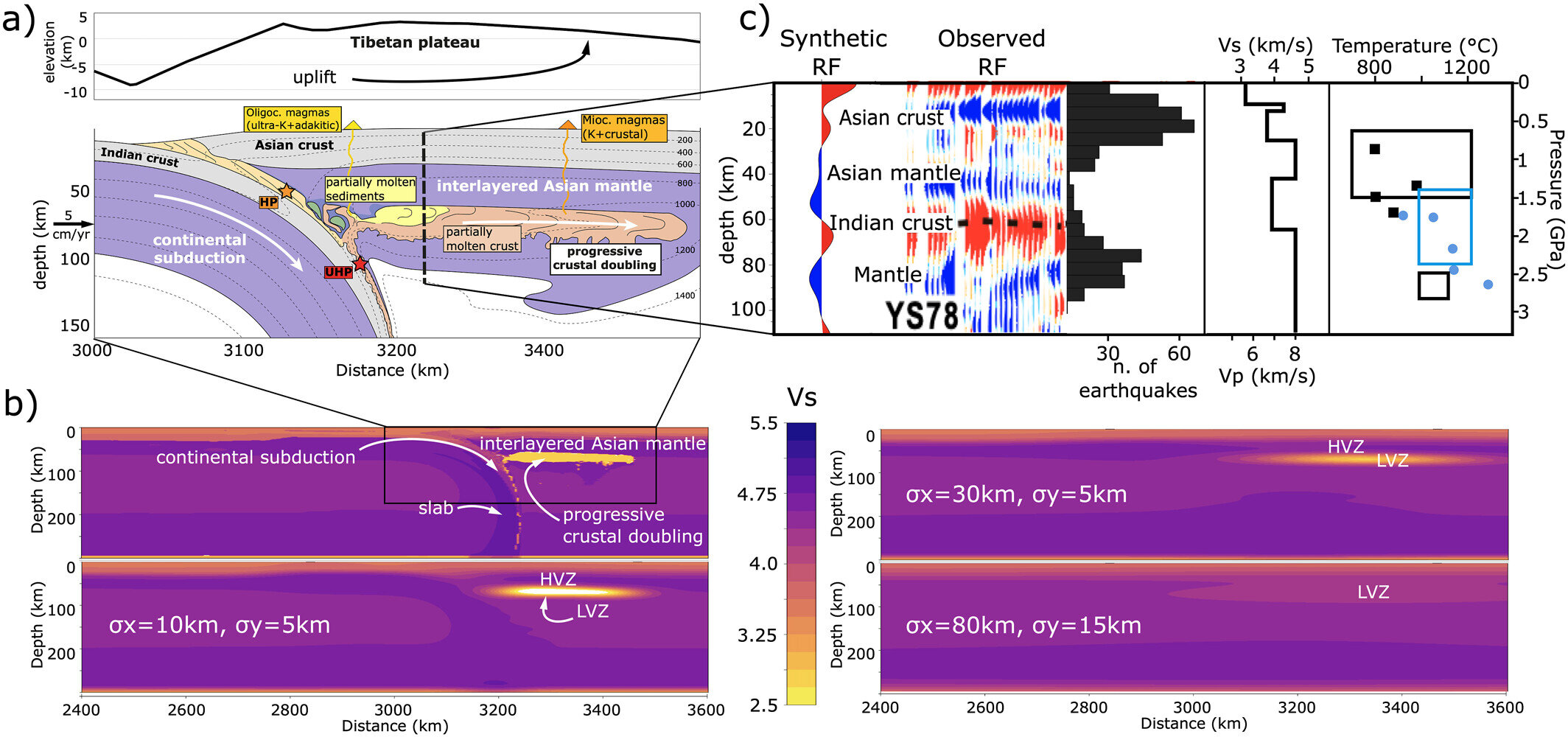

A new study challenges the century-old theory of Himalayas formation, proposing that instead of an ultra-thick crust, a 'crust-mantle-crust' sandwich formed through viscous underplating of Indian crust beneath Asian lithosphere better explains the mountain range's geology, with significant implications for understanding mountain-building processes.