"Scientists Bring Extinct Fossil Creature Back to Life as a Robot"

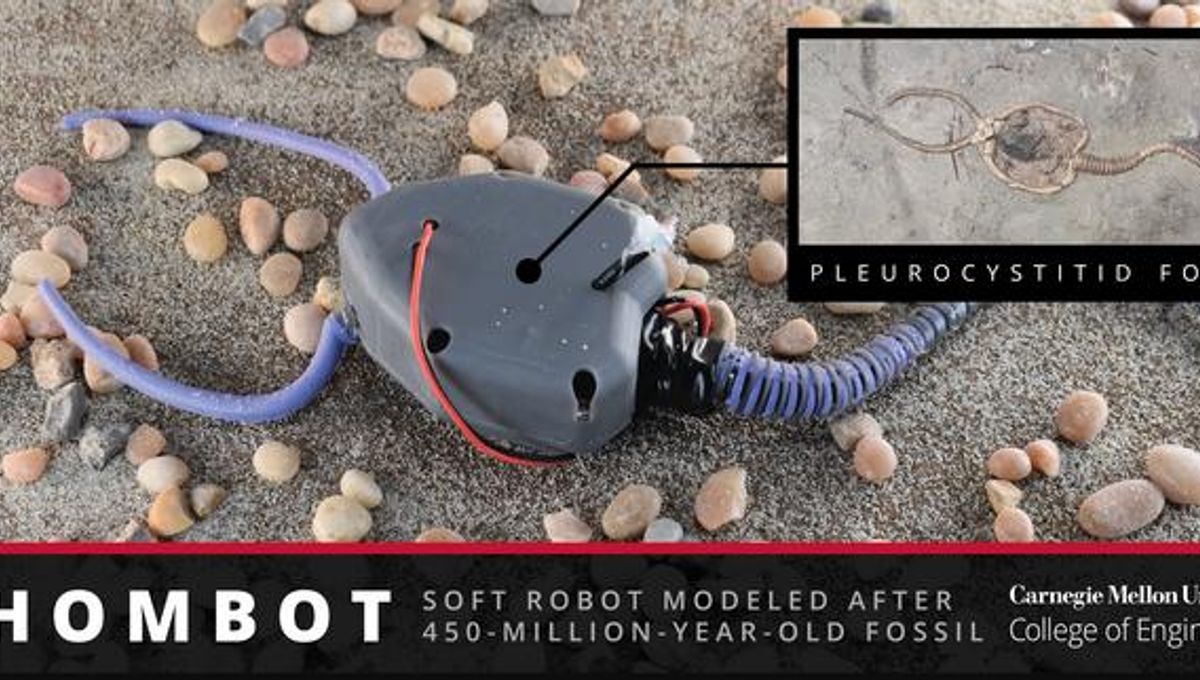

Researchers have created a soft-robot replica of the long-extinct pleurocystitid, an ancient sea creature, using principles of soft robotics and paleontology. The robot, named "Rhombot," has helped scientists understand the organism's movement and evolutionary mysteries. By combining fossil evidence with soft robotics, the study demonstrates the potential of paleobionics to study extinct organisms' locomotion and biomechanics, offering insights into the 99 percent of species that once roamed the Earth.