"Discovery of Free-Floating Binary Planetary Giants in Orion Nebula"

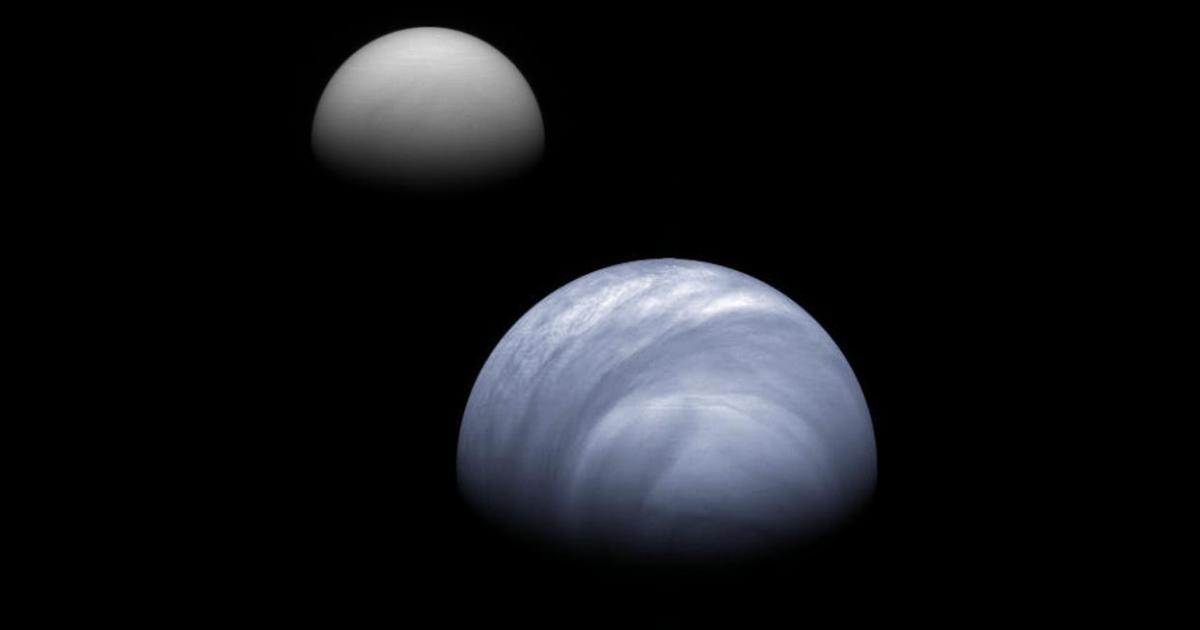

Astronomers have discovered free-floating binary planets, called JuMBOs, in the Orion Nebula using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). These Jupiter-Mass Binary Objects (JuMBOs) are not associated with stars and have masses similar to giant Jupiter-like planets. The discovery challenges current theories of star and planet formation, as these wide free-floating planetary-mass binaries do not fit within our understanding of how stars and planetary systems form. Further research is needed to understand the mechanism responsible for the unexplained radio emissions from these binary planets, and the discovery raises the possibility of these binary planets hosting moons that could potentially support life.