63 Days in a Dark Cave Reshaped Our Understanding of Biological Clocks

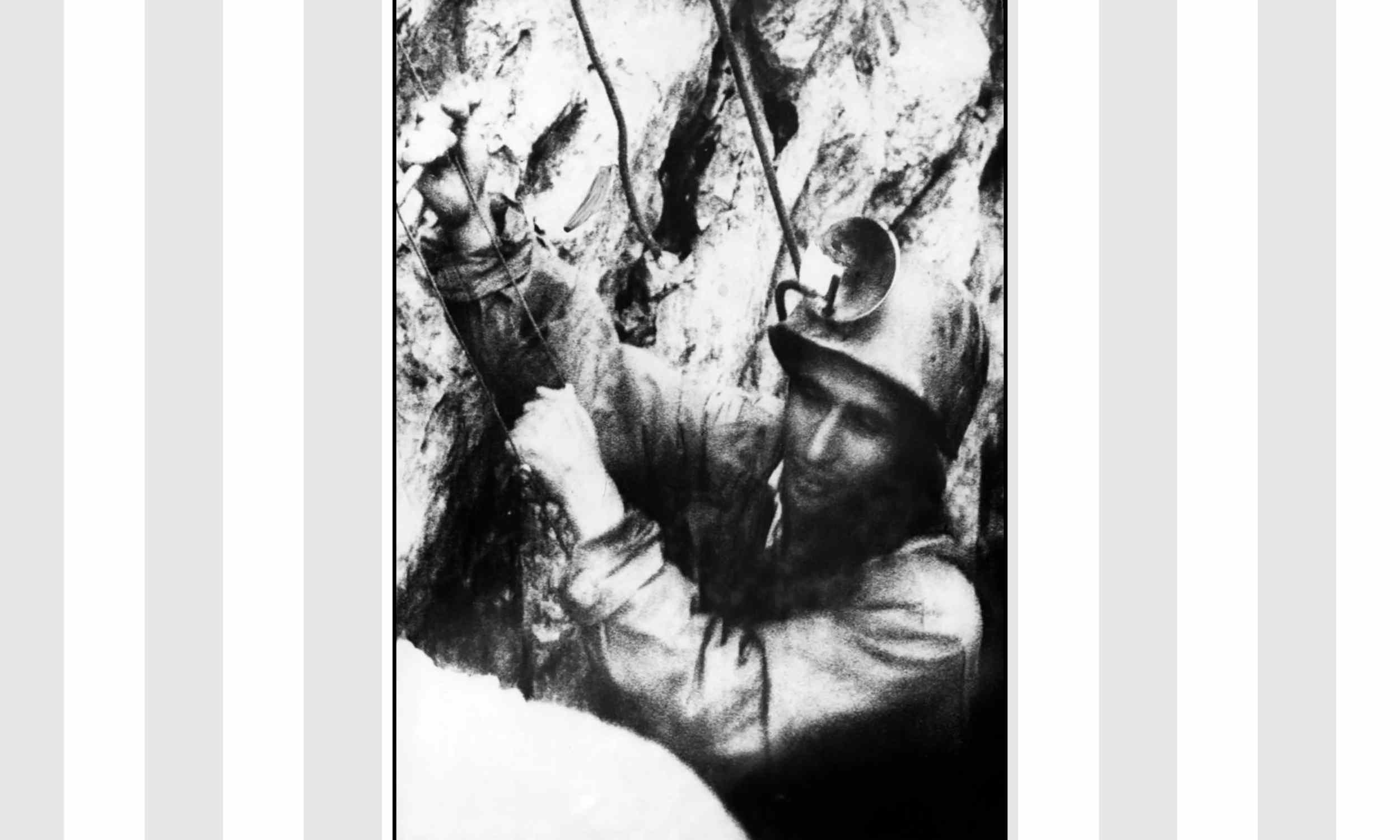

In 1962, Michel Siffre spent 63 days in a French cave with no time cues, revealing that humans have an internal circadian clock that can run free from the 24-hour day. His findings helped launch chronobiology, informed spaceflight and military confinement protocols, and continue to influence modern research on timing in medicine and astronaut missions. The data remain a reference point for agencies like NASA and ESA, even as the concept of biological time alignment guides current experiments and clinical chronotherapy.